When citizenship is politicised – the plight of the stateless in Malaysia

Of all the tragedies to befall the stateless community in Malaysia, perhaps the greatest one is that they are treated as little more than a political gimmick, a useful way to earn votes as election season swings around. In May 2017, with the 14th General Election around the corner, MIC President Dr. S Subramaniam announced the Mega MyDaftar campaign to reach out to undocumented citizens of Indian descent. The campaign ran from 3 to 26 June 2017, and received some 2500 applications.

Whilst the initiative on its own is commendable, there are obvious questions to be asked. Why was this project launched by Dr S. Subramaniam (he is the Minister of Health) and supported by MIC when citizenship registration exercise should be the mundane day-to-day job of the National Registration Department (NRD). The NRD should also be undertaking targeted or mobile registration from time to time without the need for a campaign backed by MIC – unless of course the impression aimed for is that – MIC can help the poor stateless Indian community to acquire citizenship documents.

When successful applications are processed, as seen from previous MyDaftar campaigns, there will be the glitzy photo ops with the Prime Minister flanked by the MIC President presenting citizenship documents to successful applicants. Needless to say, this creates the impression that citizenship is something that is bestowed upon the applicants – by the government, and through the support of government political parties, when it should be a matter of a constitutional right i.e. citizenship acquired by operation of law, and through the day-to-day dealings with the NRD.

Malaysian? Prove it

Denied the right to citizenship, many stateless individuals cannot access the basic rights and social services including education and healthcare, that ordinary citizens enjoy or take for granted despite being born and permanently residing in the country all their lives.

The battle for citizenship documentation for these people is long and arduous. It is not uncommon to begin this journey at childhood, and to emerge from it a young adult with all the lost opportunities. Without formal education, they are deprived of the possibility of proper employment in adulthood and relegated to menial labour and other odd jobs.

They live a life of exploitation and poverty, trapped and with no means to acquire a better living and existence. This status is passed on to the next generation: with stateless parents, children are also stateless, and the problem perpetuates across generations, all of which leads to serious social problems.

In Peninsular Malaysia, the descendants of many Indian plantation workers maintain the same stateless status as their ancestors, and so too their children to this day. Indigenous peoples in Sarawak are also affected by statelessness, burdened by the high cost of repeated travel to the city when the NRD should be conducting mobile registration. Some are required to produce DNA test to prove their familial ties or to bring village chief from the interior to the city in order to attest their applications.

The excessive bureaucratic red tape in their path gives the lie to any pretension the government may have about resolving statelessness. The process is long drawn out simply because the NRD refuses to see them as Malaysian citizens in need of help, but instead places an unreasonable and oftentimes unrealistic burden of proof upon them to show that they are, in fact, Malaysian.

There are myriad and overlapping reasons why some are stateless: parents’ own uncertain citizenship status and lack of documents (stretching back to pre-Merdeka), poverty, birth at home, abandoned children, unregistered marriages, ignorance, apathy, and fear of authorities and fines due to delay in registration.

As a consequence, many children are not properly registered after birth, leading to the inability to acquire the MyKad although some may acquire the red permanent resident card or other lesser identity documents.

There is no genuine NRD effort to register the affected communities nor is there any special procedure to facilitate their registration despite knowing the historical inequities and the context of their present circumstances. They would still be asked to fulfil the complicated form and criteria, and provide lengthy supporting documents despite knowing they would have difficulties in complying.

When they come back with incomplete information or documentation, instead of lending a sympathetic hand, to help them acquire those missing or incomplete documents, the NRD casts to the wayside those who cannot meet their strict requirements.

After repeated attempts, delays, and spiralling cost – as they are also asked to travel to Putrajaya or to the state NRD headquarters in order to resolve their applications – many just give up.

Treated as foreigners

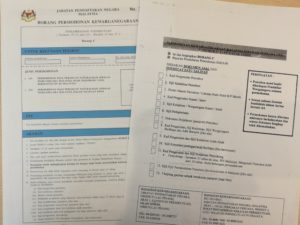

A recent protest by a group of parents and PKR leaders at the NRD office in George Town highlighted the inherent bias when processing citizenship documentation of stateless applicants. Where most Malaysians would expect to qualify for citizenship by operation of law under Article 14 of the Federal Constitution, the form provided upon request to the stateless applicants is that of an application for citizenship by naturalisation under Article 19. Since these stateless people are treated like foreigners, correspondingly, they have more onerous prerequisites that come with a foreigner applying for Malaysian citizenship.

The insistence of the NRD in going through this citizenship naturalisation process betrays either a fundamental lack of understanding of the Constitution and the circumstances of these stateless individuals or altogether more sinister motives.

In the case of children, Article 15A affords special powers to the federal government to register anyone under the age of 21 as citizens. Nevertheless, it should be noted that application for citizenship under Article 15A is discretionary and can drag on for several years. These lost years can never be recovered.

Hence, it is perfectly clear now why these people have remained stateless as the NRD from the very onset has viewed them with a sceptical eye, as foreigners claiming to be Malaysians when there is no real concern they are imposters.

Their application is not to be naturalised as Malaysian citizen but to confirm their citizenship status as Malaysian. These applications should be processed as a matter of right, by operation of law but instead, they become a discretionary process, and hence the creation of the MyDaftar campaign to link the grant of citizenship with support of government political parties.

Requiring political will

To toy with the lives of people for the sake of political gain is despicable. It should not be the case that a lucky portion of the stateless community is rounded up from time to time to receive the blessings of government political parties, whilst others are left in limbo and taken for years-long bureaucratic rides.

These stateless people embody the genuine and effective link that citizenship demands of them: born in Malaysia to at least a Malaysian parent, living all their lives in Malaysia, and without any link to any other countries. What else do NRD want?

By sheer bad luck and circumstances beyond their control, stateless Malaysians have been unjustly prevented from accessing the rights and opportunities that are afforded to full-fledged Malaysians. We cannot restore to them the years they have lost, but we can ensure they need not suffer any more than necessary.

The failures of the NRD must be brought to light and efforts made to expedite existing applications. In the longer term, a sustained push to identify stateless persons, should be conducted and their cases in turn, evaluated more equitably.

The tragedy of Malaysia’s statelessness is a mark of shame for us as a country, but it does not have to remain so. Change is certainly possible – all it takes is political will for a change in policy, for citizenship not to be politicised, and for the NRD to start treating stateless applicants more kindly, as Malaysians instead of as foreigners.

By Eric Paulsen, Executive Director of Lawyers for Liberty